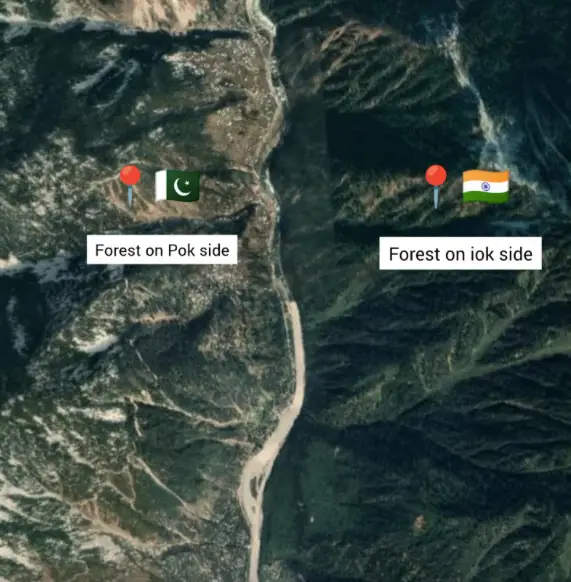

On one side, lush green forests. On the other, barren slopes. The satellite view of Neelum Valley isn’t just about trees, it is a striking reflection of Pakistan’s governance crisis and an urgent call for innovation.

A Tale of Two Slopes

A widely shared Neelum Valley satellite image, captured through Google Earth along the Line of Control (LoC), tells two very different stories.

On the Indian side, forests remain dense and protected, benefiting from stricter laws and more consistent enforcement. On the Pakistani side, the slopes are stripped bare as a result of decades of unchecked logging, illegal timber trade, and a governance system unable to hold the so-called Timber Mafia accountable.

This image is more than just a comparison of greenery. It is a visual audit of our institutions, incentives, and the price of neglect.

Pakistan’s Shrinking Forests

The numbers behind the picture are just as alarming as the view itself.

- Pakistan has only 4.7% forest cover, one of the lowest in Asia.

- Just 1.37 million hectares of natural forests remain.

- Satellite data shows that hundreds of hectares are still lost every year.

The consequences are devastating. Deforestation leads to soil erosion, flash floods, biodiversity loss, and reduced water storage. After a cloudburst in AJK on August 14, floodwaters carried uprooted timber into the Nauseri Dam near Muzaffarabad, raising alarms about upstream forest destruction and its cascading impacts.

Beyond the Environment: A Systemic Issue

Deforestation is not merely an environmental concern. It is an economic and governance crisis. Forests are natural infrastructure, providing flood control, water regulation, and soil stability. Their destruction weakens agriculture, damages dams, and increases the vulnerability of cities to climate shocks.

For Pakistan’s entrepreneurs, the lesson is clear: when governance fails, mafias step in. When systems collapse, innovation becomes not just an opportunity but a necessity.

Also Read

The Rise of Fintech Startups in PakistanWhat Has Worked Glimpses of Hope

Despite the grim reality, there are promising examples that show Pakistan can fight back.

- Billion Tree Tsunami (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa): Successfully restored around 350,000 hectares of forest, earning international recognition.

- Ten Billion Tree Tsunami (National): Backed by the UN Environment Programme, the initiative crossed 1 billion trees planted, although progress has slowed amid political challenges.

- Delta Blue Carbon (Sindh): A pioneering project restoring over 73,000 hectares of mangroves, generating carbon credits purchased by global companies such as Salesforce. It is now one of the world’s largest blue carbon projects.

- Urban Forest Karachi: Entrepreneur Shahzad Qureshi has transformed empty plots into dense native forests using the Miyawaki method, helping reduce heat and absorb floodwater in one of Pakistan’s most climate-stressed cities.

These initiatives prove that change is possible when science, finance, and community engagement align.

Startup Opportunities in Climate and Forest Tech

The Neelum Valley image may expose our failures, but it also highlights where entrepreneurs can step in. Pakistan’s startup ecosystem has an opportunity to turn deforestation into a problem worth solving one that blends technology, sustainability, and new business models. Here are five areas where founders can make a tangible difference:

1. Forest Monitoring & Verification

One of the biggest gaps in Pakistan’s forestry projects has been credible monitoring. Trees are planted, but survival rates are often disputed, and results are rarely transparent. Startups can bridge this gap by building Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) platforms that use a mix of satellite imagery, IoT sensors, and blockchain.

For example, drones or remote sensing can map forest growth, IoT soil sensors can track moisture and tree health, while blockchain can store tamper-proof records of survival rates. Such platforms not only ensure transparency for governments and NGOs but also make it easier for global investors and climate financiers to trust and support Pakistan’s reforestation efforts.

2. Timber Supply Chain Tracking

Illegal logging thrives because timber is easy to move and even easier to launder into legal markets. Startups can help change that by building supply-chain tracking systems. Think QR codes or NFC tags attached at the point of harvest, verified along the chain through transporters, mills, and retailers.

Much like food traceability startups, timber traceability can cut out the Timber Mafia by allowing only verified, legal wood to enter the market. Over time, builders, furniture makers, and exporters could demand verified timber — forcing the industry to shift toward accountability.

3. Community Incentive Models

For many rural households, wood isn’t just timber, it’s their main source of cooking fuel and heating. Until alternatives are viable, deforestation will continue. Here lies an opportunity for startups to build clean energy businesses that directly reward communities for forest protection.

This could be in the form of affordable biogas plants, solar cookstoves, or biomass pellets that replace firewood. Revenue-sharing or incentive schemes could tie community adoption to forest health meaning the better the forest survives, the more rewards flow to local households. By aligning household economics with conservation, startups can make communities allies rather than victims of deforestation.

4. Urban Resilience Projects

Deforestation isn’t just a rural crisis, cities are feeling the heat too, literally. Urban startups can play a role by offering micro-forests as a service to housing societies, industrial estates, and malls.

Inspired by the Miyawaki method, these dense, fast-growing native forests cool cities, absorb stormwater, and improve biodiversity. Imagine a subscription model where businesses or gated communities pay to plant and maintain a micro-forest, while also receiving environmental credits or branding benefits. This creates both social impact and a scalable business opportunity in urban sustainability.

5. Carbon Finance Platforms

Reforestation has the potential to not only restore ecosystems but also generate revenue through carbon credits. However, accessing international carbon markets requires credibility, verification, and scale areas where startups can build platforms.

By connecting verified local projects (like community forests or mangrove restoration) with global buyers seeking offsets, startups can unlock new financial streams for conservation. Projects like Delta Blue Carbon in Sindh have already proven that global corporations are willing to buy credits if the project is credible. Tech-enabled platforms could replicate this model across other regions of Pakistan, bringing global climate finance directly to local communities.

Together, these five opportunity areas point toward a new frontier: climate-tech entrepreneurship in Pakistan. The Neelum Valley image may symbolize decay, but for the startup ecosystem, it can also symbolize the chance to build sustainable businesses that protect resources, empower communities, and create long-term value.

These are not just environmental ventures, they are business models that solve systemic problems while creating sustainable revenue streams.

Also Read

Lessons for Pakistan’s Startup EconomyThe Way Forward

Neelum Valley’s satellite image is more than a viral post. It is a mirror showing us the cost of broken systems, corrupt incentives, and years of neglect.

But it also points to a future that is still possible. With innovative startups, transparent monitoring, and sustainable financing models, Pakistan can not only restore its forests but also rebuild trust in systems that people believe have long failed them.

For the next generation of entrepreneurs, this is not just about planting trees. It is about planting accountability, sustainability, and resilience at the core of Pakistan’s growth story.

The question is, will we choose to look away from the image or use it as a blueprint to build better systems?

FAQ

Because it visibly shows the difference in forest cover between the Indian and Pakistani sides of the Line of Control. On Pakistan’s side, decades of illegal logging and weak enforcement have led to barren slopes making the image a powerful symbol of governance failure.

As of 2022, Pakistan has only about 4.7% forest cover, among the lowest in Asia. Just 1.37 million hectares of natural forests remain, with hundreds of hectares being lost every year due to illegal logging, fuelwood use, and poor management.

Yes. Examples include the Billion Tree Tsunami in KP, the Ten Billion Tree Tsunami nationally, the Delta Blue Carbon project in Sindh (restoring mangroves and selling carbon credits), and Urban Forest initiatives in Karachi using the Miyawaki method. These show that with innovation and accountability, Pakistan can reverse deforestation trends.