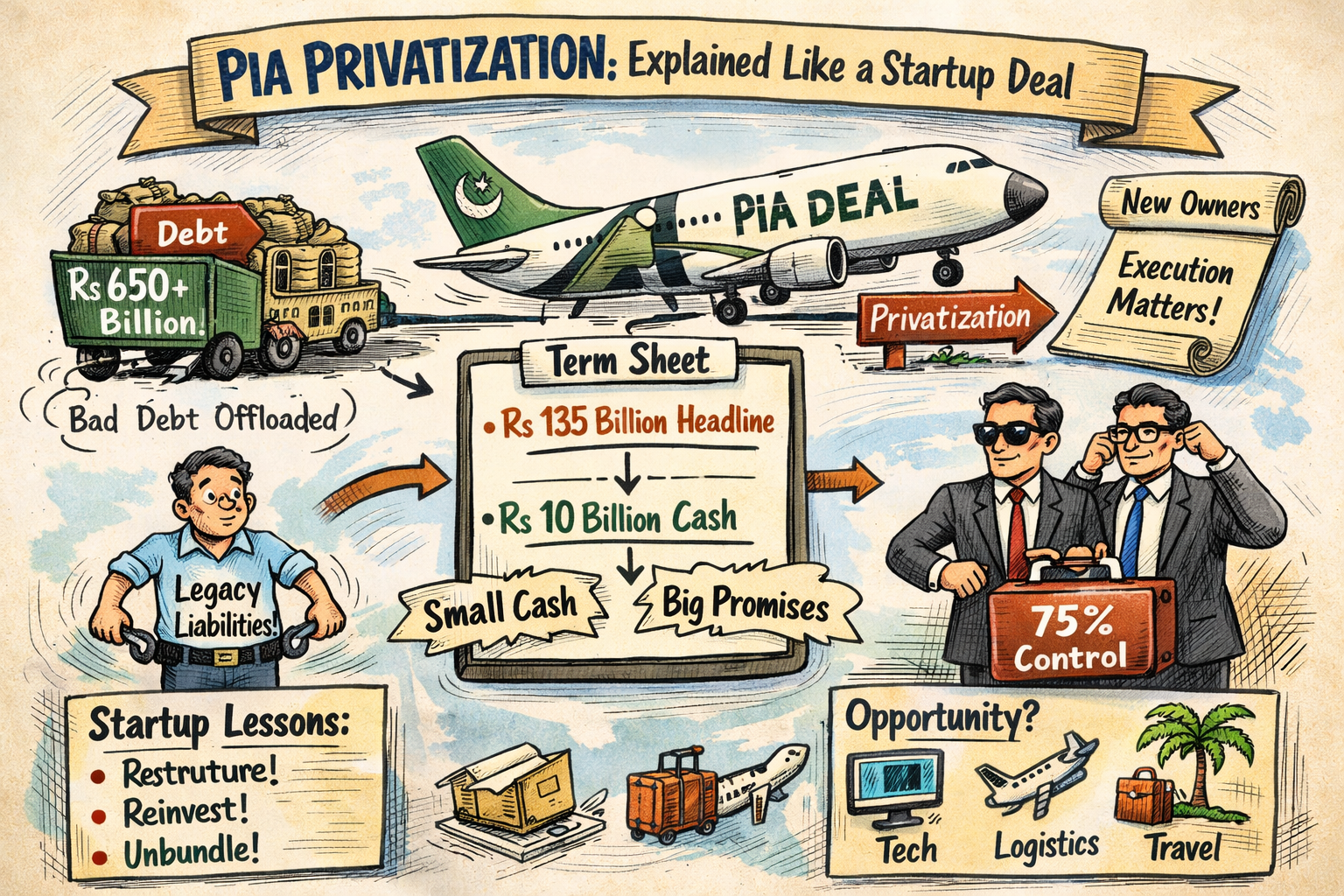

PIA wasn’t really sold for Rs135 billion. When you break it down like a startup deal, the story looks very different.

For weeks, the headline has been repeated everywhere: PIA sold for Rs135 billion.

But anyone who has ever raised capital, negotiated a term sheet, or restructured a struggling company knows one thing: headline numbers rarely tell the real story.

Strip away the politics, nationalism, and outrage, and Pakistan International Airlines’ privatization looks far less like a traditional asset sale and far more like a late-stage turnaround deal. One with legacy debt, ring-fenced liabilities, conditional capital injections, and carefully managed optics.

In other words, this wasn’t a clean exit.

It was a control transfer with a rewritten balance sheet.

Let’s explain it like a startup deal.

The Headline Valuation vs. the Real Economics

The widely quoted figure of Rs135 billion creates the impression that the government received a large cash windfall. It didn’t.

From a deal-structure perspective, the transaction breaks down into two very different components:

- A small upfront cash payment (reported to be around Rs10 billion)

- A much larger commitment to future capital injection, earmarked for reviving the airline fleet expansion, operations, and restructuring

For founders, this should sound familiar.

This is the equivalent of a startup announcing a “$50 million deal,” where:

- Only $5–10 million is paid upfront

- The rest is tied to milestones, reinvestment, or future spending obligations

The headline is designed for optics.

The economics are designed for survivability.

Why the Government Had to Clean the Balance Sheet First

No serious investor was going to take over PIA with Rs650–700 billion in accumulated liabilities sitting on its books.

So the state did what investors do in distressed acquisitions:

- Legacy debt was carved out

- Loss-making baggage was parked elsewhere

- The airline was presented with a “cleaner” balance sheet

This is not unique to Pakistan.

It is standard practice in turnarounds globally.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

The debt didn’t disappear. It was socialized.

Taxpayers remain responsible for decades of accumulated mismanagement, while new owners inherit a far more viable operating entity.

In startup terms, this is like:

- Writing off bad debt

- Shutting down unviable verticals

- Resetting the cap table

before bringing in new majority shareholders

Control, Not Cash, Was the Real Prize

The government did not optimize this deal for maximum immediate revenue.

It is optimized for offloading operational responsibility.

By selling 75% control, the state effectively exited day-to-day management of:

- Fleet decisions

- Route strategy

- Hiring and procurement

- Commercial risk

For a loss-making SOE that had become politically radioactive, this mattered more than headline cash.

From an investor’s perspective, this is also rational:

- Control enables execution

- Execution creates upside

- Upside justifies long-term capital injection

This is why calling this a “sale” misses the point.

It was a governance reset.

The Technical Debt Problem At National Scale

Every founder understands technical debt:

- Bad early decisions

- Compromised processes

- Talent mismatches

- Incentives that no longer make sense

PIA is technical debt accumulated over decades.

Privatization does not magically erase this. It merely changes who is responsible for fixing it.

The success or failure of this deal will hinge on whether:

- Management autonomy is genuinely protected

- Political interference stays out

- Aviation policy aligns with commercial realities

Changing ownership without fixing the system is a mistake founders learn early. Nations learn it late.

What the Deal Means for the Startup Ecosystem (But No One Is Talking About)

The most under-discussed aspect of PIA’s privatization is second-order opportunity.

Large-scale privatizations don’t just affect the company being sold. They create whitespace around it.

If executed properly, this could unlock:

- Aviation software and analytics providers

- Travel fintech and dynamic pricing platforms

- Cargo and logistics startups

- MRO (maintenance, repair, overhaul) services

- Tourism-tech integrations

Globally, airline restructurings have spawned entire supplier ecosystems.

Pakistan has historically failed to capture this spillover value.

That is the real missed opportunity to watch.

The Core Question Isn’t “Should PIA Have Been Privatized?”

That debate is largely settled.

The real question is:

Can Pakistan execute a turnaround without repeating the same structural failures just under new ownership?

Founders know the answer depends on systems, not slogans:

- Governance

- Incentives

- Policy consistency

- Talent freedom

- Competitive neutrality

Ownership change is the easy part.

Systems change is the hard one.

Why This Story Matters Beyond Aviation

PIA is not just an airline.

It is a case study in how Pakistan handles failure at scale.

If this privatization succeeds, it becomes a template for SOE reform.

If it fails, it reinforces the belief that structural problems cannot be outsourced.

For Pakistan’s startup and business community, the lesson is familiar:

You can’t build a winning company or a competitive economy by changing shareholders alone. You have to change how decisions are made.

And that is the real deal behind the Rs135 billion headline.